低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的相结构、机理和性能

低密度 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢:相结构、机制和性能

低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的相结构、机理和性能

介绍了低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的组织相、显微组织特征及其相关温度和高温性能。 在工业结构件中使用这些低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢可减少结构重量高达18%。 本文介绍了最新的合金设计策略,特别关注L'12(Fe,Mn)3AlC晶粒(κ氮化物)和B2型富Ni/Ccu析出物的最新相结构和变形行为。 未来的科学和技术挑战是将这种钢作为工业应用的结构材料。

关键词:低密度钢; 相结构; 变形机制; 强化机制; 加工硬化机制; 机械性能; 高温热性能; κ-氮化物

1. 序言

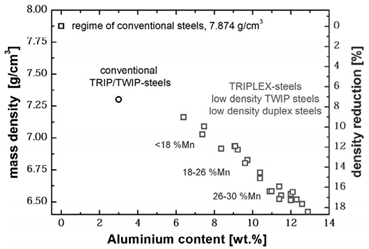

低密度铁锰铝碳钢是用于车辆、化工和客机行业的新型结构材料。 这种钢在高温和高温下表现出优异的拉伸热性能,并且还可以将预制构件的重量减轻18%,因为该钢的铝含量较高(每1wt.%Al钢密度降低1.3%,参见图1[1]),此外,这种钢还表现出令人着迷的性能,如高能量吸收行为、高硬度、高温和高温硬度、优异的疲劳性能和良好的抗氧化性能。 [2-13]由于Mn、Al对热性能和抗氧化性能的影响,最初从经济角度出发,于20世纪80年代和90年代开发了Fe-Al-Mn-C钢来替代Fe-Cr-Ni-C碳素钢。 在过去的六年里,低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢由于其在轻量化车辆碰撞结构和高温工业结构部件中的应用而引起了广泛的关注。 由于Fe-Mn-Al-C钢中存在一些无序和有序的fcc和bcc相,突出了优异的热性能和化学性能的结合,可以通过选择组织控制来调整,特别是对于L'12 Fe,Mn)3AlC晶粒(κ氮化物)和B2型富Ni/Cu析出物的相变结构和变形行为为开发先进低密度钢提供了新的合金设计策略。 这种钢表现出的优异的硬度和脆性组合归因于奇异的强化和应变强化机制,例如有序强化、相变诱导塑性 (TRIP)、孪生诱导塑性 (TWIP)、剪切诱导塑性 (SIP) 和动态滑带增强功能。 [2,5,8,10,11,14,15]本文总结了用现代技术实验突出的Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的相关物相,以及强化和应变强化机制的理论研究。 。 概述了机械特性,并剖析了微观结构对其的影响。 未来的科学和技术挑战是构建低密度铁锰铝碳钢作为工业应用的结构材料。 下面以重量百分比给出钢的成分和合金纯度。

图1 Al浓度对低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢密度增加的影响

2.相结构

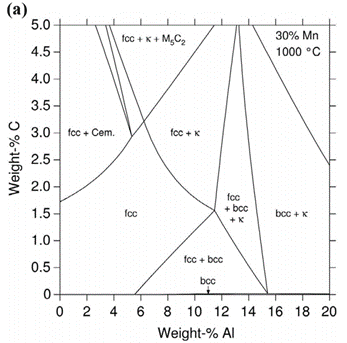

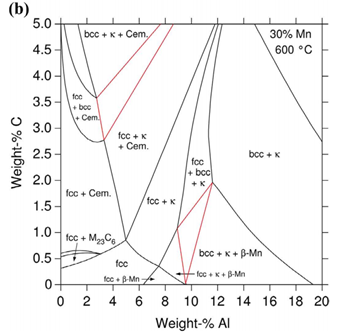

低密度 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢的特点是三相(bcc-铁素体/fcc-奥氏体)或两相(铁素体+奥氏体)结构,具体取决于合金纯度和形变处理,具有复杂分布的基体。 在低密度钢中,最受关注的烧蚀是MC、M3C、M23C6和M7C3型基体,以及有序fcc(L'12)(Fe,Mn)3AlC基体,即κ-氮化物。 [16-19] 一般来说,用于估计 Fe-Mn-Al-C 碳化物等温截面的相图主要来自热力学数据库,并有不同的描述。 相图显示了Al浓度扩大铁素体相范围并抑制奥氏体相范围的总体趋势。 该图还预测,对于给定的 Al 浓度,奥氏体区随着 C 和 Mn 浓度的降低而减小。 图 2 显示了根据 PrecHiMn-4 数据库估算的奥氏体 Fe-30Mn-Al-C 钢在 1000 °C (a) 和 600 °C (b) 时的等温相截面。 [19]该图表明,奥氏体在低Al浓度下是稳定的(。随着C浓度的降低,高铝钢中奥氏体稳定性也急剧增强(例如,添加1wt.%C可以降低奥氏体的稳定性)相,其铝浓度高达9~10wt.%Al)。该图也表明Fe-Mn-Al-C钢奥氏体中κ相的稳定需要高铝和高碳。在600℃ ,Al>5wt.%,C>1wt.%产生κ型氮化物。低Al浓度(Al,可以产生回火体和M23C6型基体而不是κ型氮化物。有趣的是,这个图还阐明了奥氏体、铁素体、渗碳体和κ-氮化物在特定的Al和C浓度范围内是稳定的。例如,在高C浓度(>1wt.%C)下,κ-氮化物和氮化物可以发生组合模式,另一方面,在高Al浓度(>9wt.%Al),铁素体、奥氏体和κ相在有限的C浓度范围内内部稳定。 这一特点表明,为了促进奥氏体中κ氮化物的析出,必须严格控制C的纯度和固溶温度。 可以看出,在1000℃时,κ-氮化物只能在C和Al的浓度较大时才稳定,如C>1.5wt.%-Al>12wt.%和C>3wt.%。 %-Al>6wt.%,与实际成分范围无关。

图2 根据PrecHiMn-4数据库估算的Fe-30Mn-Al-C奥氏体钢在1000℃(a)和600℃(b)时的等温截面

3、低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的组织分类

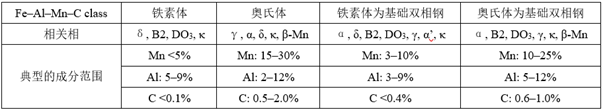

从碳化物相组织角度看,低密度Fe-Al-Mn-C钢可分为铁素体钢、奥氏体钢和双相钢三种类型。 表1总结了最相关的显微组织和成分特征,Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的显微组织特征如下。

表1 低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的显微组织和成分特征

3.1. 铁素体 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢 [20-24]

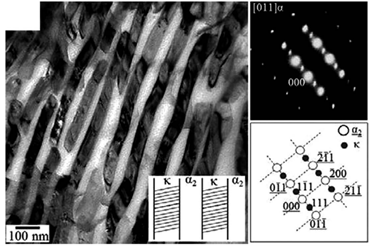

铁素体Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的Mn浓度较低(<5wt.%),Al浓度为5-9wt.%,C浓度较低(<0.1wt.%)。 该钢中还可以添加Si、Nb、Ti、V、Ta等元素,以促进MC型基体的析出和晶界的细化。 在热加工条件下,该钢具有沿铣削方向延伸的δ-铁素体碳化物结构,从而形成带状结构。 在板坯加工过程中,δ-铁素体直接从液态形成,根据合金的纯度,奥氏体相在热机械处理后发生γ→α′马氏体转变,产生宏观马氏体带。 [21,23] Al浓度强烈改变该类铁素体碳化物的晶体结构,当Al>7wt.%时,δ相发生有序转变,产生复杂的立方结构,如FeAl物性的B2 Fe3Al 物理测量的结构相和 DO3 结构相。 根据铝浓度的不同,δ-碳化物相可以是A2无序FeAl、B2有序FeAl和DO3有序Fe3Al。 通过热轧和微合金化Nb、Ti、V、B等元素细化碳化物。 在该钢中,由于δ相和κ基体之间的高晶格失配(晶格失配~6%),κ氮化物在界面上是半共格的,导致结构的球状延伸,见图3。 (011)δ//(111)κ-氮化物的取向关系对应于Nishiyama-Wasserman关系,即(011)δ//(111)κ。 最近对铁素体 Fe-3.2Mn–10Al-1.2C 钢 κ 基体的物理结构进行原子探针断层扫描 (APT) 分析,突出显示了晶粒的非物理计量结构。 [25]该报告解释的κ氮化物的非物理测量是因为部分取代Al的Fe或Mn位于面心立方结构晶胞的角部。 根据C浓度和冷却速度的不同,可以生成粗大的κ氮化物。

图3 Fe-3.0Mn-5.5Al-0.3C铁素体钢中层状α相/κ氮化物组织的明场TEM像和衍射图

3.2. 奥氏体 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢 [9,26–41]

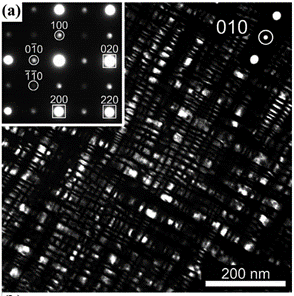

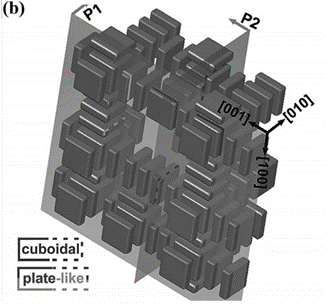

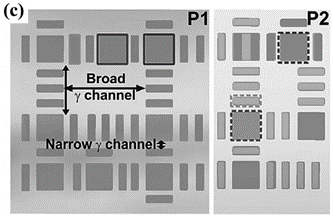

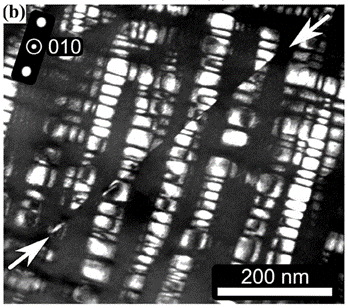

奥氏体Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的特点是高Mn浓度(15-30wt.%)、高Al浓度(2-12wt.%)和高C浓度(0.5-2.0wt.%)。 此类钢为低密度钢,在热加工条件下呈现完全等轴奥氏体组织。 合金的析出行为和γ→α相变特征取决于冷却速率以及Al和C的浓度。特别是,高Al浓度(>9wt.%)促进畸变铁素体的生成,有序B2和DO3被分离出来。 [9] 从热学角度来看,κ 氮化物(L1'2 相)最为相关,尽管钢中其他基体(即 M23C6M7C3、M3C)的析出也会影响热性能。 在奥氏体Fe-Mn-Al-C钢中,κ氮化物的产生需要较高浓度的Al和C,即Al>5wt.%和C>1wt.%(见图2)。 K氮化物是相干和半相干沉淀(晶格失配),与奥氏体具有立方到立方晶胞的相关系,即[100]κ//[100]γ和[010]κ// [ 010]伽玛。 最近,原子探针解剖断层扫描(APT)与基于密度泛函理论(DFT)的估计相结合揭示了奥氏体 Fe-29.8Mn-7.7Al-1.3C 钢中非物理 κ 氮化物的结构,[35 ,37]特别是,APT已经证实亚晶格已经耗尽了间隙原子C和取代原子Al。 这种效应归因于 MnγAl 反位点(假设与周围碳化物处于热力学平衡)在相干 κ 氮化物引起的压缩弹性应变下的能量积累。 κ氮化物分布是立方体和板状沉淀物的复杂三维排列,沿三个正交方向半径约为10至50 nm。 通过透射电子显微镜(TEM)解剖了κ-氮化物的二维分布,结果表明纳米级析出相沿边带分布方向,图4(a)[15]原子探针断层扫描(APT ) 分析了κ-氮化物的三维分布。 最近发现κ-氮化物以不同颗粒宽度的堆叠形式密集分布,图4(b)、4(c).15),κ-氮化物沿同一堆叠分布,颗粒宽度约为2 -5nm(图4(c)中的窄γ通道)。 沿不同层分布的κ氮化物颗粒宽度约为10-40 nm(较宽的γ通道如图4(c)所示)。

图4 Fe-30.4Mn-8Al-1.2C奥氏体钢在2600℃退火24小时后κ氮化物的分布(a):TEM暗场图像; (b):基于APT数据的κ-氮化物的三维形貌及形貌排列图; (C); κ氮化物分布沿方向的二维投影,如图(b)

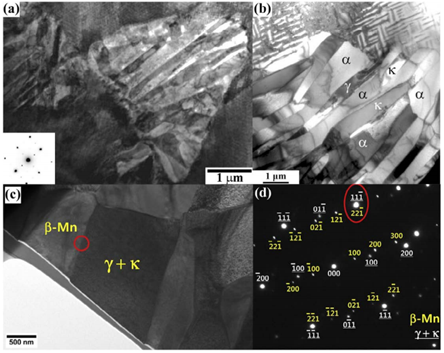

在Fe-Mn-Al-C奥氏体钢中,通过亚稳γ相的顺序脊柱分解,即物理调制,可以大量析出κ氮化物(体积分数高达40%)。 第二个反应是γ到亚稳态(Fe,Mn)3AlCx(x<1)L12相(κ'-氮化物)的短程有序(SRO),随后κ'-氮化物有序转变为κ-氮化物。 [26,27,29,31]κ'-氮化物具有与κ-氮化物一致的晶体结构,并且C原子没有完全占据它们应有的间隙。 特别是当Al和C浓度分别>10wt.%和>1wt.%时,旋节线分解动力学和κ-氮化物密度都随着Al和C浓度的降低而降低。 在450~650℃室温范围内延长时效时间时,κ氮化物晶格常数降低,奥氏体晶格参数降低。 这些效应促进了 κ-氮化物相干性的丧失。 在650-800°C的固溶温度下,粗大的κ-氮化物倾向于沿着氢键沉淀,形成层状γ/κ结构,图5(a)。 根据钢的成分和固溶条件,可以通过不同类型的反应产生这种基体,例如晶胞转变和共析反应,[28,30,41]氢键κ-氮化物与相邻碳化物具有平行的性质。 方位关系。 在沉淀的早期阶段,κ-氮化物沿着氢键产生离散颗粒。 在(γ+κ)或(γ+α+κ)区域进一步发生固溶,该基体转变成沿氢键连续分布的薄膜,并生长成相邻的碳化物,如图5(b)所示。 当Al浓度较高(>6wt.%)时,β-Mn通过相变κ→α+β-Mn沿氢键析出,[34,36,42]图5(c),5(d)物质和α-bcc颗粒。 γ/β-Mn取向关系为(111)γ//(221)β; (01-1)γ//(01-2)β; (-211)γ//(-542)β。 [39] 高Al浓度奥氏体Fe-Mn-Al-C钢在低温(800℃)时效过程中发生γ→α转变,[32] 生成的铁素体相富含有序B2和DO3组织,这使钢的性能恶化。钢的热性能。

图5(a):Fe-30.5Mn–8Al-1.2C钢奥氏体钢在600℃固溶96小时,[33]κ基体沿两个相邻奥氏体晶粒的明场TEM图像γ1和γ2碳化物边界之间的析出(b):Fe-18Mn-7.1Al-0.85C钢固溶体在650℃保温100小时,明场TEM图像αγ/κ层状组织; [30](C):Fe-31.4Mn-11.4Al-0.9C奥氏体钢在550℃退火500h后β-Mn析出物的明场TEM图像,(D):在γ-碳化物/β- Mn中间相边界衍射模型。 [39]

3.3. 双相 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢 [3,8–12,32,43–50]

双相Fe-Mn-Al-C钢具有复杂的多相组织,由δ-铁素体、α-铁素体、奥氏体、κ-氮化物和κ'-氮化物组成。 高Mn浓度的铁素体双相钢可产生α′马氏体和贝氏体。 由于锰、铝合金的纯度较高,镀锌过程中熔融组织中该元素发生宏观烧蚀,产生宏观带状组织。 通过调节热机条件,可以控制组织相的结构、尺寸、体积分数和分布。 从碳化物相组织角度看,低密度双相钢可分为铁素体基双相钢和奥氏体基双相钢。 该钢的显微组织特征如下。

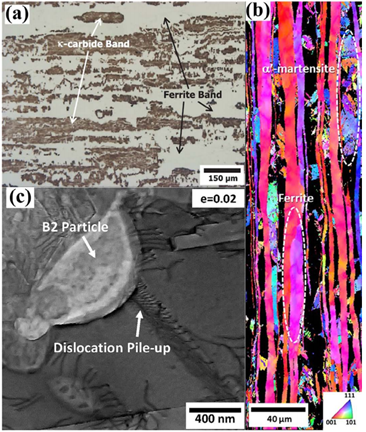

铁素体基双相钢富含中等Mn浓度(3-10wt.%)、Al浓度(5-9wt.%)和低C浓度(<0.4wt.%),[10,44,48]钢沿铣削方向具有δ-铁素体和奥氏体的复杂双峰带结构,如图6(a)所示。 奥氏体带的相结构很大程度上取决于Mn浓度和固溶处理。 健康)状况。 奥氏体部分或全部转变为沿母相γ氢键或在δ/γ界面处产生的(α+κ)带状场。 层状(α+κ)结构的特点是κ-氮化物的细长管状半共格晶格。 当Mn浓度较高时,γ→α+κ的分解受到抑制,发生γ→α'的马氏体转变。 [46,47]以奥氏体体为主的双相Fe-Mn-Al-C钢具有较高的Mn和Al浓度(Mn>25wt.%和Al>9wt.%),Al浓度为5~12wt.% ,C浓度为0.6~1.2wt.%[3,8,8,11,12,32,43.,45,47,49,50],在调质状态下均表现出足够的奥氏体组织。 在500-800℃温度下时效后,可沿奥氏体氢键产生复杂的铁素体能带结构。 另一方面,铁素体基双相钢具有复杂的δ铁素体带结构和沿轧机方向延伸的奥氏体带,如图6(b)所示。 从图中可以看出,奥氏体可以发生应变诱导的α′-马氏体转变。 除了生成L'12κ-氮化物之外,最近还提出了几种促进有序B2型沉淀相生成的沉淀策略。 添加约3-5wt.%的镍和铜会导致奥氏体区析出非剪切B2型析出物,从而改善机械性能。 [8,12,50]作为反例,图6(c)显示了Fe-12Mn-7Al-0.5C-3Cu钢中B2富铜析出物中界面位错的积累。 根据合金纯度和固溶条件,铁素体带材可能富含 B2 析出物、κ-氮化物和奥氏体碳化物。 κ-氮化物是由γ→α+κ的共析分解产生的。

图6(a)铁素体基双相钢Fe-3.5Mn-5.8Al-0.35C钢的光学显微照片; [44](b):0.3C钢镀锌奥氏体双相Fe-8.5Mn-5.6Al-EBSD相图; [47] (c) Fe-12Mn-7Al-0.5C-3Cu 钢在 830°C 退火 1 分钟后应变为 0.02,[12] 富含 CuB2 析出物的明场 TEM 图像。

4.变形热处理

Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的单晶硅一般在1100℃-1250℃的水温下均化1-3小时,然后在850-850℃的水温下镀锌成2-5mm长度的棒材。 1000°C。 。 镀锌后,镀锌棒在500-650℃温度范围内冷却1-5小时,空冷或水冷至温度。 在铁素体钢中,由于δ-碳化物碳化物尺寸大且窄,镀锌棒不能用作最终产品。 为了控制碳化物规格、织构和析出行为,镀锌棒首先进行热轧,然后在 700-900°C 的温度下固溶。 对于铁素体基双相钢,最终可以使用奥氏体渗碳工艺。 在奥氏体钢中,镀锌棒可以直接快速冷却至500-750°C的水温范围,然后进行温和冷却。 另外,镀锌带钢可快速冷却至温度,然后等温溶解。 镀锌后的冷却速度是避免有害晶间卡帕氮化物形成的关键。 奥氏体钢热轧产品一般将热轧棒材在900-1100℃温度范围内进行退火,然后进行快速渗碳。 沉淀硬化一般是在500-700℃的温度范围内固溶处理5-20小时。

5.性能

本节回顾了低密度 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢最相关的工程性能。 然而,由于这种钢作为潜在的结构材料的新颖性,现有的一些工程性能的文献综述是可用的。 总是有限,本节剖析低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的温度和高温拉伸性能、冲击硬度、能量吸收和耐腐蚀性能。

5.1. 温度热特性

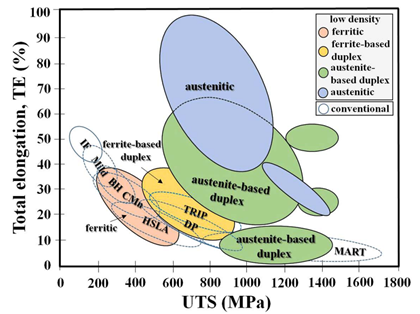

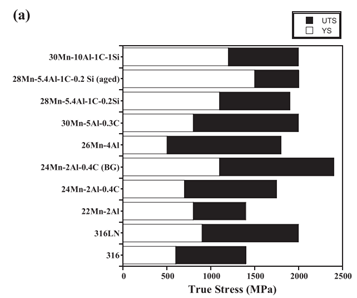

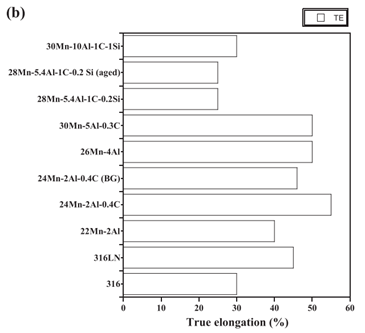

Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢在一定温度下表现出广泛的热性能,具体取决于合金成分和加工路线。 图 7 概述了几种 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢在一定温度下的伸长率 (TE) 和伸长硬度 (UTS) 图。 [2,3,5,6,8-12,21,23,24,26,32,33,38,43-45,47-62]。 特别是,图 7 显示了以下功能:

图7 几种低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的温度伸长率(TE)和极限拉伸硬度(UTS)曲线。 研究了几种常规高硬度钢的拉伸性能,即IF(无间隙原子钢)、低碳钢、BH(烘烤硬化钢)、碳锰钢、HSLA(高强度低合金)、TRIP(相变钢) -诱导塑性))、DP(双相)和 MART(马氏体)

-铁素体Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的拉伸性能与烘烤硬化(BH)钢、低合金C-Mn钢和HSLA钢相似。 该钢的延伸硬度为450-500MPa,延伸率为15-30%。 当Al>7wt.%时,即使在热轧过程中,短程有序(K1态)的产生也会导致板材的延性裂纹。

——铁素体基双相钢位于第一代先进高硬度钢(如TRIP钢、双相钢和CP钢)的上限。 其延伸硬度一般为600-800MPa,延伸率为15-40%。

-奥氏体基双相钢比铁素体基双相钢具有优异的拉伸性能。 这种钢的 UTS 通常为 600-1400MPa,延伸率 TE 为 20-60%。 特别是,添加 Ni 和 Cu 的奥氏体双相钢表现出机械硬度(屈服变形>1.0GPa;UTS>1.5GPa;中等伸长率:20-30%)、高 Al 浓度钢(Al> 10wt.%)富含高体积分数的纳米级κ-氮化物、粗粒间κ-氮化物和α-颗粒。 这些析出行为导致钢的高硬度(~1400MPa)和有限的TE(以及高机械各向异性。

-奥氏体钢表现出良好的拉伸性能组合,即UTS为600-1100MPa,TE为40-100%。

低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的拉伸性能与基本强化和变形机制有关。 该机制的主要特点如下:

-铁素体和铁素体基双相钢的拉伸性能主要由铁素体的应变硬化能力[3,9,43]和粗晶间κ氮化物的生成控制。 钢中形成的位错亚结构是铁素体钢的典型特征。 [9,11,59]在铁素体基双相钢中,奥氏体碳化物可以发生应变诱导的α'-马氏体转变,这可以在高挠度水平下产生变形孪晶。 由于 TRIP(转变诱导塑性)和 TWIP(孪生细胞诱导塑性)效应的激活,这种效应导致应变强化能力增加。 TRIP 效应的效率取决于亚稳奥氏体的晶体取向及其对应变诱发马氏体生成的热稳定性。

- 奥氏体双相钢的拉伸性能由奥氏体应变强化能力、可剪切 κ 氮化物和不可剪切 B2 析出物的生成以及铁素体碳化物的尺寸控制。

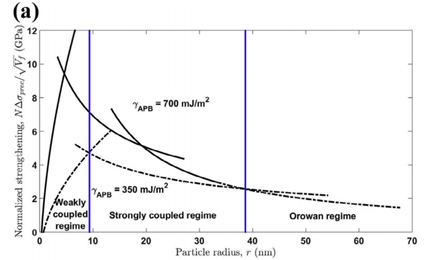

——奥氏体钢的拉伸性能较强,如渗碳强化,是因为颗粒剪切和析出有序强化,即奥罗万位错环。 姚等人。 最近分析了Fe-Mn-Al-C奥氏体钢的强化机制,他们的分析总结在图8(a)中。 该图显示归一化硬度(归一化与体积分数,Vf)

反相边界 (APB) 能量 γAPB 的两个值,作为平均沉淀物粒径 r 的函数。 通过从头计算法估算了这两种不同相结构的κ氮化物能量,一种含碳γAPB约为700mJ/m2,另一种不含碳γAPB约为350mJ/m2,从图中可以看出,随着析出颗粒尺寸r的减小,强化机制从弱耦合颗粒剪切转变为强耦合颗粒剪切。 据悉,从图中可以看出,对于高r值(r>40nm),主动强化机制为Orowan位错环强化。 图中还表明,当γAPB值较高时,增强体峰值挠度减小,使用粒径来划分不同硬度的情况减少。 值得强调的是,对于常规规格的κ氮化物(10-40 nm),从图中可以看出,颗粒剪切是主要的强化机制,这与实验观察结果一致,[2,4,6, 9,15,38,45]图8(b)显示了κ硬质合金剪切Fe-30.4Mn–8Al-1.2C钢的示例,拉伸真应变0.02,[15]Orowan位错环仍然对此有贡献颗粒间区域的宽度,即广泛的γ通道,如图4(C)所示。

图 8(a):在 350(实线)和 700(虚线)mJ/m2 γAPB 时,归一化 κ-氮化物增强与粒径、r、γAPB 的函数关系; [15=](b):暗场TEM图像像κ氮化物剪切Fe-30.4Mn–8Al-1.2C钢一样,拉伸应变高达0.02真应变。 [15]

Fe-Mn-Al-C钢优异的奥氏体加工硬化行为归因于平面位错亚结构的产生和演化,[3,5,6,14,38,45]以及动态滑移带细化机制碳化物,应变下的平面滑带[2,14,15,38],[14,15]在低铝κ无晶界奥氏体钢中,变形孪晶只能在高挠度下实现 活化,形成的能力进一步的应变强化。 [5] 这种位错组织的生成机制主要与短程有序(SRO)团簇和κ氮化物的剪切有关。 哈斯等人。 [38]最近提出,这种剪切机制对滑移面软化效应具有类似的影响,从而对不断演化的位错构象也有类似的影响。 在无κ氮化物奥氏体钢中,平面位错结构主要是碳浓度对位错横滑移频率的影响,[5]以及短程有序(SRO)对位错滑移的影响。 [5,14,38]在含碳κ氮化物奥氏体钢中,平面二维位错结构的产生归因于κ氮化物的剪切,图8(b)。 演化出的平面位错结构形成的应变强化率足够高,足以补偿位错剪切和κ氮化物碎裂形成的负应变强化率,另外位错运动拖出碳和其他元素导致γAPB降低。 κ-氮化物。 [15]

5.2. 高温热性能

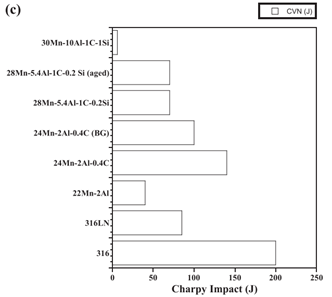

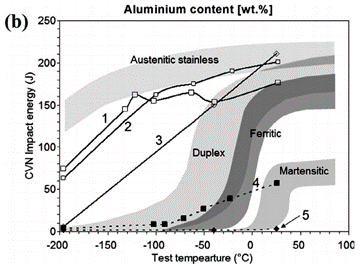

Fe-Mn-Al-C奥氏体钢的高温热性能与传统碳钢相当。 一般来说,Fe-Mn-Al-C奥氏体钢的高温热性能主要取决于奥氏体到马氏体γ→α′的稳定性,[63]基体行为、位错和孪晶结构。 [64]对新估计的Fe-Mn-Al-C相图的进一步探索,结合最新的沉淀研究,可能会打开高温低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的空间设计图。 例如,李等人。 [64]最近提出了一种热力学技巧,纳米级κ氮化物和富铌晶粒的异质成核分布,从而产生优异的高温热性能。 图9显示了几种Fe-Mn-Al-C钢在77k湿度下的屈服硬度(YS)、拉伸硬度(UTS)、延伸率(TE)和夏比冲击功,[51,52, 63–65]挠度值是真实的挠度值。 为了进行比较,图中包含了传统碳钢的热性能。 图9(a)和9(b)显示Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的YS约为1GPa,77K温度下的UTS约为1.8-2.0GPa,真实伸长率为40-50% ,与316LN(15Cr-12.5Ni-1.5Mn-2.5Mo-0.2Si-0.15N)碳钢成材率相当。 另一方面,Fe-Mn-Al-C钢在77K室温下表现出更宽的夏比V型缺口(CVN)冲击功(6-140J),高于316L(~200J),见图9( C)。 一般来说,无碳κ氮化物奥氏体钢比含碳κ晶粒奥氏体钢表现出更高的CVN值。

图9 低密度Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的高温热性能。 (a):屈服硬度(YS)和伸长硬度(UTS); (b):拉伸伸长率(TE); (c):夏比 V 型缺口 (CVN) 冲击能

5.3.冲击硬度

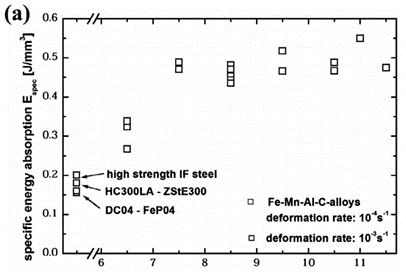

与传统的深冲钢(如 DC04、HC300LA 和高硬度 IF 钢)相比,低密度 Fe-Mn-Al-C 钢表现出高能量吸收行为,见图 10(a)。 [1]当Al>为7wt.%时,Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的Espec值约为0.5J/mm3; 比传统深冲钢(0.16-0.25J/mm3)高约50%,Espec是给定湿度和高应变率下单位体积的变形能。 在高应变速率下,Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的能量吸收因剪切带的产生而增加。 Fe-Mn-Al-C钢的冲击硬度与显微组织密切相关,很大程度上取决于κ-氮化物的产生和δ-铁素体的存在。 [13] Al浓度在调节该钢的冲击硬度方面起着重要作用。 当Al时,发生Fe3C和M7C3基体晶粒的析出,使钢的塑性和硬度变坏。 When Al>7wt.%, because of the decrease of κ-nitride volume fraction and the generation of δ-ferrite, the mechanical hardness increases, but the plasticity and impact hardness increase. The former is due to the large increase in impact hardness due to the incongruous deformation between the γ and δ phases. Figure 10(b) shows the Charpy of several austenitic Fe-Mn-Al-C steels under different solid solution conditions V-notch (CVN) impact energy as a function of test water temperature. [13,66] In the melt-treated state (curve 3), Fe-Mn-Al-C steels exhibit high impact energy at temperatures similar to those of austenitic carbon steels. In the aged state (curves 4 and 5), the CVN impact energy increases moderately with the test air temperature, reaching values similar to those of the duplex steel.

5.4.Corrosion resistance

The corrosion resistance of low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steel in water environment is comparable to that of conventional high-hardness steel, but not as good as 304 carbon steel. [67] Adding aluminum will form a positive anti-corrosion effect, and cannot reduce the resistance to deflection corrosion cracking behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-C steel. [68] On the other hand, adding Cr to reduce carbon improves the corrosion resistance of Fe-Mn-Al-C alloy, but limits its thermal properties, mainly because of the dual phase; 微观结构。 [67,69]

6. 未来的挑战

In the past six years, the basic research of Fe-Mn-Al-C steel has been very active. Research fields such as alloy design, [1,8,10,12,32] thermodynamic database, [16–19] structural analysis, [25,31,34,35,37,39,40] precipitation behavior, [26~ 29,41,42] phase transitions, [30,36] and deformation and strengthening mechanisms [2-6,11,14,15,33,38,46,50,55,60,61,64] have been extensively investigation. However, there are still many open issues regarding the application of Fe-Mn-Al-C steels as structural materials for industrial applications, in the following several scientific and technical challenges for Fe-Mn-Al-C steels are to be addressed.

6.1.Technical challenges

—Steelmaking. In the smelting process of Fe-Mn-Al-C steel, adding a large amount of Mn and Al is a difficult problem to deal with. A strong physical reaction will occur between the molten steel and the refractory material, resulting in impurities and physical alloy errors. For example, during the slab process, the silicon carbide at the bottom of the molten steel causes the nozzle to block the flocculation. Due to the physical reaction between the slab and the atmosphere, a large amount of dense silicon carbide will be produced on the surface of the slab. Therefore, in the slab of Fe-Mn-Al-C steel, surface defects, brittle phases and cracks will occur, as well as hydrogen production. And so on, in order to overcome this defect, it is necessary to implement a new slab process route.

-handicraft Research. Studies on the hot rolling and recrystallization structure of Fe-Mn-Al-C steel, the texture transition of rolling and subsequent recrystallization, and the control of carbide specifications have not been elaborated, and those are optimized processing settings under industrial conditions. key conditions.

-Mechanical behavior. The analysis of mechanical properties, such as fracture behavior (especially at high temperature), mechanical anisotropy (especially for double carbide steels), and fatigue properties has not been exhaustively inspected. Fe-Mn-Al-C steel is the key as a structural material.

—Hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen embrittlement is one of the main technical problems in the research of high hardness steel. Dissecting the effect of hydrogen on the thermal behavior of low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steel is crucial for the industrial application of this steel. In Fe-Mn-C steel, the addition of Al can reduce the hydrogen embrittlement of austenitic Fe-Mn-Al-C steel. [70–75] This effect is attributed to the fact that Al increases the solubility of hydrogen in Fe-Mn-Al-C steels, increasing the permeability and diffusivity of hydrogen. There are many different types of microstructural interfaces and phase structures in low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steels, which may exhibit different hydrogen capture efficiencies, resulting in complex hydrogen embrittlement behaviors. For example, estimates based on density functional theory (DFT) predict that the hydrogen capture efficiency of κ-nitrides strongly depends on the concentrations of C and Mn. [76] This estimation suggests that with proper control of precipitation, κ-nitrides become hydrogen traps. Further studies are required to elucidate the efficiency of microstructural interfaces such as twin boundaries, dislocation structures, B2 precipitates, and κ-nitrides on hydrogen capture.

6.2. 科学挑战

-Short Range Order (SRO). The appearance of short-range ordered SROs is often considered to be a planar feature of the dislocation structure at the initial stage of transformation of Fe-Mn-Al-C grain boundary-free austenitic steels. The size, thermal stability, and structural stability of SRO clusters are still unclear. From an experimental point of view, dissecting the effect of SRO and SRO clusters on plasticity is a challenging task, and it is worthy of further research on the effect of SRO on plasticity to provide new alloy design strategies.

- The phase structure, precipitation behavior and strengthening mechanism of the Cu/niB2-rich phase in Fe-Mn-Al-C double carbide steel are crucial for the microstructure control of this precipitate phase and the construction of new alloy design strategies .

- Thermodynamic behavior of microstructural interfaces. Low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steels, very double carbide steels, contain different types of homophase (twin boundaries and dislocation structure) and heterophase interfaces (ferrite/austenite, austenite/B2 , Austenite/L1′2, Ferrite/B2, Ferrite/L1′2). The mechanical and thermal behavior of the microstructural interface has not been studied in detail, and the thermal behavior of the microstructural interface is crucial for understanding the mobility of this interface and its effect on recrystallization behavior and grain boundary growth. On the other hand, the thermal behavior of the microstructural interface (eg, twin/dislocation interaction, precipitate/dislocation interaction, and crack propagation behavior along the microstructural interface) is the key to understanding the nucleation and propagation of this steel plasticity. , critical to damage nucleation and rupture behavior.

-Alloy controlled strain-enhanced strengthening mechanism. Several strain-enhancing mechanisms are observed in low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steels, the plasticity of which is related to the complex interaction of different microstructure phases and the thermal stability of those microstructure phases. In order to complete robust alloy design strategies, the analysis of alloy schemes for strain strengthening mechanisms should be explored. This is a challenging task because of the presence of different types of microstructural interfaces, very heterogeneous interfaces, which can cause local physical elemental gradients to occur.

7. 推理

Low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steel is a potential structural material for vehicles, aircraft and high-temperature industries. Its combination of excellent chemical and mechanical properties can reduce the weight of the structure by up to 20%, making this steel as a structural material for heavy-duty crashworthy car body structures and cryogenic industries. Fe-Mn-Al-C steel exhibits an excellent combination of thermal properties at high temperature and high temperature because of the presence of some disordered and ordered fcc and bcc phases, which can be tuned by selective microstructure control. In the past six years, a great deal of research activity has been aimed at dissecting the underlying deformation mechanisms and determining the crystal structure, such work as L'12(Fe,Mn)3AlC grains (κ-nitrides) and B2-type Ni/ New insights into the crystal structure of Cu precipitates and their deformation behavior have been provided, and this activity has led to new alloy design strategies for the development of advanced low-density steels. This paper proposes a novel strain hardening mechanism to explain the excellent strain hardening of this steel by shearing short-range ordered clusters and κ-matrix to generate an expanded planar dislocation organization. There are still some scientific and technical challenges in the construction of low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steels as structural materials for industrial applications, especially in the areas of alloy design, steelmaking, processing, mechanical properties, and hydrogen embrittlement. This challenge makes low-density Fe-Mn-Al-C steel an ideal steel for further scientific and technological research.

致谢

The authors would like to thank the NIMS donor for the financial support of the project "Principle elucidation of the relationship between nanoscale structure and interface dynamics".

参考

1)D.Raabe,H.Springer,I.Gutierrez-Urrutia,F.Roters,M.Bausch,J.-B.Seol,M.Koyama,P.-P.ChoiandK.Tsuzaki:JOM,66(2014) ,1845.

2)K.Choi,C.-H.Seo,H.Lee,SKKim,JHKwak,KGChin,K.-T.ParkandN.J.Kim:Scr.Mater.,63(2010),1028.

3)H.Ding,D.Han,Z.CaiandZ.Wu:JOM,66(2014),1821.

4) G. Frommeyer and U. Brüx: Steel Res. Int., 77 (2006), 627.

5) I. Gutierrez-UrrutiaandD. Raabe: ActaMater., 60 (2012), 5791.

6)I.Gutierrez-UrrutiaandD.Raabe:Scr.Mater.,68(2013),343.

7)H.Kim,D.-W.SuhandN.J.Kim:Sci.Technol.Adv.Mater.,14(2013),014205.

8)S.-H.Kim,H.KimandN.J.Kim:Nature,518(2015),77.

9)K.-T.Park,SWHwang,CYSonandJ.-K.Lee:JOM,66(2014),1828.

10) SS Sohn, K. Choi, J.-H. Kwak, NJ Kim and S. Lee: ActaMater., 78 (2014), 181.

11) SS Sohn, H. Song, B.-C. Suh, J.-H. Kwak, B.-J. Lee, NJ Kim and S. Lee: ActaMater., 96 (2015), 301.

12) H. Song, J. Yoo, S.-H. Kim, SS Sohn, M. Koo, NJ Kim and S. Lee: ActaMater., 135 (2017), 215.

13) S. Chen, R. Rana, A. Haldar and RK Ray: Prog. 马特。 Sci., 89 (2017), 345.

14)E.Welsch,D.Ponge,SMHHaghighat,S.Sandlöbes,P.Choi,M.Herbig,S.ZaeffererandD.Raabe:ActaMater.,116(2016),188.

15)MJYao,E.Welsch,D.Ponge,SMHHaghighat,S.Sandlobes,P.Choi,M.Herbig,I.Bleskov,T.Hickel,M.Lipinska-Chwalek,P.Shanthraj,C.Scheu,B.GaultandD.Raabe:ActaMater.,140(2017),258.

16)K.Ishida,H.Ohtani,N.Satoh,R.KainumaandT.Nishizawa:ISIJInt.,30(1990),680.

17)K.-G.Chin,H.-J.Lee,J.-H.Kwak,J.-Y.KangandB.-J.Lee:J.Alloy.Compd.,505(2010),217.

18)H.-J.Lee,SSSohn,S.Lee,J.-H.KwakandB.-J.Lee:Scr.Mater.,68(2013),339.

19)B.Hallstedt,AVKhvan,BBLindahl,M.SellebyandS.Liu:Calphad,56(2017),49.

20)L.Falat,A.Schneider,G.SauthoffandG.Frommeyer:Intermetallics,13(2005),1256.

21)SYHan,SYShin,H.-J.Lee,B.-J.Lee,S.Lee,NJKimandJ.-H.Kwak:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,43(2012),843.

22)Y.-U.Heo,Y.-Y.Song,S.-J.Park,HKDHBhadeshiaandD.-W.Suh:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,43(2012),1731.

23)SYHan,SYShin,B.-J.Lee,S.Lee,NJKimandJ.-H.Kwak:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,44(2013),235.

24)A.Zargaran,HSKim,JHKwakandN.J.Kim:Scr.Mater.,89(2014),37.

25)J.-B.Seol,D.Raabe,P.Choi,H.-S.Park,J.-H.KwakandC.-G.Park:Scr.Mater.,68(2013),348.

26)K.Sato,K.TagawaandY.Inoue:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,111(1989),45.

27)K.Sato,Y.InoueandK.Tagawa:Metall.Trans.A,21(1990),5.

28)CNHwang,CYChaoandT.F.Liu:Scr.Metall.Mater.,28(1993),263.

29)WKChoo,JHKimandJ.C.Yoon:ActaMater.,45(1997),4877.

30)W.-C.fú:JOM,66(2014),1809.

31)LNBartlett,DCVanAken,J.Medvedeva,D.Isheim,NIMedvedevaandK.Song:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,45(2014),2421.

32)A.Etienne,V.Massardier-Jourdan,S.Cazottes,X.Garat,M.Soler,I.ZuazoandX.Kleber:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,45(2014),324.

33)I.Gutierrez-UrrutiaandD.Raabe:Mater.Sci.Technol.,30(2014),1099.

34)K.Lee,S.-J.Park,J.Moon,J.-Y.Kang,T.-H.LeeandH.N.Han:Scr.Mater.,124(2016),193.

35)MJYao,P.Dey,J.-B.Seol,P.Choi,M.Herbig,RKWMarceau,T.Hickel,J.NeugebauerandD.Raabe:ActaMater.,106(2016),229.

36)XPChen,YPXu,P.Ren,WJLi,WQCaoandQ.Liu:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,703(2017),167.

37)P.Dey,R.Nazarov,B.Dutta,M.Yao,M.Herbig,M.Friak,T.Hickel,D.RaabeandJ.Neugebauer:Phys.Rev.B,95(2017),104108.

38)C.Haase,C.Zehnder,T.Ingendahl,A.Bikar,F.Tang,B.Hallstedt,W.Hu,W.BleckandD.A.Molodov:ActaMater.,122(2017),332.

39)K.Lee,S.-J.Park,J.-Y.Kang,S.Park,SSHan,JYPark,KHOh,S.Lee,ADRollettandH.N.Han:J.Alloy.Compd.,723(2017),146.

40)CHLiebscher,M.Yao,P.Dey,M.Lipińska-Chwalek,B.Berkels,B.Gault,T.Hickel,M.Herbig,J.Mayer,J.Neugebauer,D.Raabe,G.DehmandC.Scheu:Phys.Rev.Mater.,2(2018),023804.

41)YHTuan,CLLin,CGChaoandT.F.Liu:Mater.Trans.,49(2008),1589.

42)CYChao,CNHwangandT.F.Liu:Scr.Metall.Mater.,28(1993),109.

43)MCHa,J.-M.Koo,J.-K.Lee,SWHwangandK.-T.Park:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,586(2013),276.

44)SSSohn,B.-J.Lee,S.Lee,NJKimandJ.-H.Kwak:ActaMater.,61(2013),5050.

45)ZQWu,H.Ding,HYLi,MLHuangandF.R.Cao:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,584(2013),150.

46)C.-Y.Lee,J.Jeong,J.Han,S.-J.Lee,S.LeeandY.-K.Lee:ActaMater.,84(2015),1.

47)SSSohn,H.Song,J.-H.KwakandS.Lee:Sci.Rep.,7(2017),1927.

48)X.Li,R.Song,N.ZhouandJ.Li:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,709(2018),97.

49)D.Han,H.Ding,D.Liu,B.RolfeandH.Beladi:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,785(2020),139286.

50)MXYang,FPYuan,QGXie,YDWang,E.MaandX.L.Wu:ActaMater.,109(2016),213.

51)YGKim,JMHanandJ.G.Lee:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,114(1989),51.

52)RKYou,PWKaoandD.Gan:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,117(1989),141.

53)O.Grässel,L.Krüger,G.FrommeyerandL.W.Meyer:Int.J.Plast.,16(2000),1391.

54)Y.Kimura,K.Handa,H.HayashiandY.Mishima:Intermetallics,12(2004),607.

55)JDYoo,SWHwangandK.-T.Park:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,40(2009),1520.

56)KMChang,CGChaoandT.F.Liu:Scr.Mater.,63(2010),162.

57)CLLin,CGChao,HYBorandT.F.Liu:Mater.Trans.,51(2010),1084.

58)S.-J.Park,B.Hwang,KHLee,T.-H.Lee,D.-W.SuhandH.N.Han:Scr.Mater.,68(2013),365.

59)H.Ding,D.Han,J.Zhang,Z.Cai,Z.WuandM.Cai:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,652(2016),69.

60)SSSohn,H.Song,MCJo,T.Song,HSKimandS.Lee:Sci.Rep.,7(2017),1255.

61)J.Moon,S.-J.Park,JHJang,T.-H.Lee,C.-H.Lee,H.-U.Hong,HNHan,J.Lee,BHLeeandC.Lee:ActaMater.,147(2018),226.

62)H.Ishii,K.Ohkubo,S.MiuraandT.Mohri:Mater.Trans.,44(2003),1679.

63)SSSohn,S.Hong,J.Lee,B.-C.Suh,S.-K.Kim,B.-J.Lee,NJKimandS.Lee:ActaMater.,100(2015),39.

64)Y.Li,Y.Lu,W.Li,M.Khedr,H.LiuandX.Jin:ActaMater.,158(2018),79.

65)KTLuo,P.-W.KaoandD.Gan:Mater.Sci.Eng.A,151(1992),L15.

66)O.Acselrad,J.Dille,LCPereiraandJ.-L.Delplancke:Metall.Mater.Trans.A,35(2004),3863.

67)YHTuan,CSWang,CYTsai,CGChaoandT.F.Liu:Mater.Chem.Phys.,114(2009),595.

68)SCChang,JYLiuandH.K.Juang:Corrosion,51(1995),399.

69)GDTsay,CLLin,CGChaoandT.F.Liu:Mater.Trans.,51(2010),2318.

70)DKHan,YMKim,HNHan,HKDHBhadeshiaandD.-W.Suh:Scr.Mater.,80(2014),9.

71)EJSong,HKDHBhadeshiaandD.-W.Suh:Scr.Mater.,87(2014),9.

72)DKHan,SKLee,SJNoh,S.-K.KimandD.-W.Suh:Scr.Mater.,99(2015),45.

73)I.-J.Park,K.-H.Jeong,J.-G.Jung,CSLeeandY.-K.Lee:Int.J.Hydrog.Energy,37(2012),9925.

74)KHSo,JSKim,YSChun,K.-T.Park,Y.-K.LeeandC.S.Lee:ISIJInt.,49(2009),1952.

75)M.Koyama,E.AkiyamaandK.Tsuzaki:ISIJInt.,52(2012),2283.

76)TATimmerscheidt,P.Dey,D.Bogdanovski,J.vonAppen,T.Hickel,J.NeugebauerandR.Dronskowski:Metals,7(2017),No.7,1.

作者

IvanGUTIERREZ-URRUTIA:ResearchCenterforStrategicMaterials,NationalInstituteforMaterialsScience(NIMS),Sengen1-2-1,Tsukuba,305-0047Japan.

唐杰民2021年4月中上旬在广东宣城歙县翻译自美国刊物2021年第一期。金属材料知识有限的,翻译过程中肯定有不对不妥之处,请诸位看官给以见谅。

转载请注明出处:https://www.twgcw.com/gczx/621.html